Charles Pil Expo

English translation

Charles Pil 1867-1949 – introduction

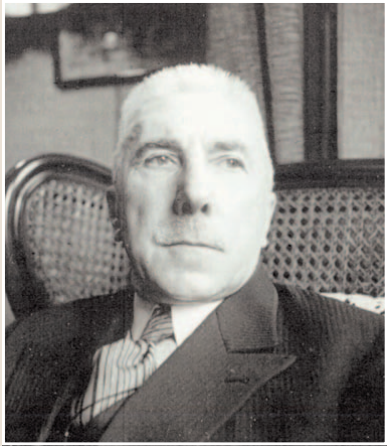

Seventy-five years ago architect Charles Pil (1867-1949) passed away in Ostend. Recognized as one of the most prolific architects in West Flanders during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Pil’s work has left an indelible mark on the region’s architectural heritage. While he is best known for his striking Art Nouveau facades, adorned with colorful glazed tiles in Ostend, his versatile portfolio spans numerous other buildings across the area. In the aftermath of World War I, Pil collaborated with architect Henri Carbon, playing a pivotal role in the region’s reconstruction efforts.

This exhibition pays homage to Charles Pil, illuminating his architectural significance and the diverse aspects of his life and work. A captivating photo display melds photography with architecture, offering a visual journey through Pil’s creations.

Additionally, a podcast featuring conversations with experts and residents of Pil’s buildings provides deeper insights into his enduring legacy.

The exhibition is a testament to a unique collaborative initiative led by the city of Oudenburg and IOED Polderrand. This extensive cooperation includes the municipalities of Nieuwpoort, Middelkerke, Gistel, and Lo-Reninge, alongside regional cultural and heritage associations such as Ginter, Hydra, and IJzervallei. Contributions from local heritage organizations, including Erfgoedkring 8460 Oudenburg, Graningate, De Plate, the Lange Nelle guides’ association, VIVES educational institution, and entities like CultuurContaCt In Dialoog, have been instrumental in bringing this comprehensive project to fruition.

Biography

From Farmer’s Son to Esteemed Architect

Charles Pil was born on December 21, 1867, in the village of Lo, to farmer Pieter Pil and shopkeeper Marie-Thérèse Ameloot. His educational journey began at the esteemed Sint-Amandusschool in Ghent and culminated with an architecture degree from the Sint-Lucas Institute. This institution was renowned for its emphasis on neogothic architectural principles and the promotion of Christian Flemish values. Among his contemporaries at the institute were notable figures such as Thierry Nolf, Jules Coomans, and Jules Carette, the latter with whom Pil would later intern. After earning his diploma, Pil embarked on his career as an independent architect on March 15, 1891.

In 1892, Pil relocated to the coastal city of Ostend, a hub of significant urban transformation. The city was blossoming with luxurious villas, hotels, and burgeoning new neighbourhoods. Pil quickly distinguished himself not only as an architect but also as a prominent figure in political and influential circles. He served as an expert witness in local courts and frequently participated as a juror in the assize court of West Flanders. In 1895, he ran as a candidate for the Catholic Party in local elections. By November 1908, Pil had become a member of the Cercle Artistique d’Ostende, and in 1910, he was one of the founding members of the Royal Architects’ Circle of West Flanders.

Throughout his later career, Pil emerged as a distinguished representative and expert in the field of architecture. He chaired the Ostend branch of the provincial Architects’ Circle and served on various juries, including those for the redesign of Ostend’s beach services and the construction of a new courthouse. In 1940, he contributed to the Urbanization Committee of Ostend.

On September 26, 1893, Charles Pil married Eugénie Samson, a Frenchwoman. Together, they had four children. The family resided in stately townhouses in Ostend and enjoyed a country retreat in Gistel.

Charles Pil passed away on September 24, 1949. His funeral was held in the intimate setting of the Sint-Pieterskerk in Lo, where he was laid to rest in the family crypt within the cemetery.

Architecture

Following the Path of Eclecticism and Neogothic Influence

Charles Pil undoubtedly ranks among the most prolific architects of the first half of the 20th century. His career spanned a remarkable range of architectural styles and projects, earning him widespread acclaim. In 1941, it was noted that virtually no street in Ostend lacked the stamp of his craftsmanship, a testament to his enduring influence on the city’s architectural landscape. The number of designs attributed to Pil exceeds 140 projects, and it is likely even higher.

In his early career, Charles Pil primarily focused on constructing villas and townhouses in the prevalent eclectic style. He skilfully catered to the desires of his clients, particularly the emerging affluent middle class who sought to express their newfound status through their homes. Eclecticism granted designers the freedom to reflect their clients’ tastes, political leanings, and cultural convictions by blending various historical styles.

Pil’s early works often featured facades with neorenaissance and baroque influences. Especially in Ostend, his designs predominantly consisted of row houses with plastered facades. In contrast, in Oudenburg, he created both row houses and detached dwellings. These buildings were characterized by meticulously crafted brick facades, incorporating natural stone as well as innovative materials like coloured and glazed bricks, metal, and glass for decorative elements.

Typically, the front facades received extensive ornamentation, while the side and rear facades remained more functional and less exuberantly adorned. For commissions with a clear Catholic influence, Pil drew upon neogothic principles he had learned, adhering to the architectural principles he had mastered.

Inspired by Nature

Around 1900, Charles Pil began to infuse Art Nouveau elements into his facade designs, marking a distinct evolution in his architectural style. These Art Nouveau-inspired facades are characterized by the use of white or beige glazed bricks, often accented with tiles in vibrant colours such as sky blue or olive green.

For affluent clients, Pil went further, incorporating decorative tile panels featuring floral and figurative motifs. These panels often included tiles displaying house names and construction years, adding a personalized touch to the buildings. Although cladding a facade with glazed tiles was relatively expensive, it offered significant advantages in durability and aesthetic appeal when expertly applied.

Pil also competently used natural stone for accents and intricate details like window frames. The elegant forms of Art Nouveau, inspired by organic shapes found in plants and flowers, were seamlessly translated into natural stone. However, iron was the preferred material for depicting these natural forms due to its malleability. It could be skilfully forged and was used for features like balcony railings, enhancing the overall aesthetic with its delicate yet sturdy presence.

The use of tiles as facade cladding was architecturally innovative in Ostend, particularly during the first decade of the 20th century. Unlike the more common eclectic designs, these Art Nouveau-inspired facades were relatively rare in the city. Behind these striking facades often lay interiors influenced by historical styles.

The Rise of High-Rise Buildings

Following World War I, Charles Pil and Henri Carbon formed a dynamic partnership, becoming highly sought-after for their reconstruction expertise. Their collaboration extended beyond the immediate post-war rebuilding efforts, as they undertook numerous projects in Ostend. Among their notable contributions were the construction of several apartment buildings, playing a pivotal role in advancing high-rise architecture in the seaside town.

These apartment complexes, often designed with ground-floor retail spaces, mirrored the burgeoning accessibility of coastal tourism in the post-war era. The introduction of Sunday rest in 1905 and the increasing feasibility of beach vacations for many Belgians after the war led to a surge in coastal visits. Consequently, many apartments were developed as investment properties. Despite their commercial nature, Pil and Carbon devoted significant attention to the aesthetic and architectural integrity of these buildings.

The duo’s use of reinforced concrete, a material gaining popularity at the time, showcased their proficiency with cutting-edge construction techniques. This technical expertise also cemented their reputation as forward-thinking architects. Their innovative approach to materials and design underscored their commitment to modernity and excellence in architecture.

In addition to their residential and commercial projects, Pil and Carbon received significant commissions from religious institutions. They designed the monastery and chapel of the former Sint-Jozefslyceum in Ostend and managed expansion works in the same area. Furthermore, they were engaged by the Zusterkens der Armen to construct a new convent, underscoring their versatility and ability to address diverse architectural needs.

While they collaborated on numerous projects, both architects maintained individual practices, continuing to contribute uniquely to the architectural landscape.

Clientele

Architect for the Affluent Middle Class

Charles Pil catered to a diverse and distinguished clientele, with the affluent urban bourgeoisie as his primary patrons. These clients sought Pil’s architectural expertise to set themselves apart through the design and grandeur of their homes. Pil himself, a member of the prosperous middle class in Ostend, was deeply embedded in socio-political circles where many of his early clients were also prominent figures.

In 1902, Pil was commissioned by Louis-Charles-Henri Masureel to construct a stately notary’s residence in Koekelare. That same year, both Pil and Masureel served as jurors for the assize court of West Flanders, alongside Notary Janssens from Oudenburg, who also engaged Pil to design a notary’s house. Pil had a particularly close relationship with the Laroye merchant family, constructing three houses for them in Oudenburg, including one for his daughter Edith, who married Willy Laroye.

In Ostend, Pil’s clientele was extensive and affluent. Throughout his career, he designed several residences on the prestigious Prinses Clementinaplein. Among his notable clients were Abel Carette, a Brussels industrialist and contractor; Flore Blondiau, a trader from Aalst; and Edmond Brys, a Ostend contractor.

After World War I, Pil’s focus shifted primarily to reconstruction efforts. Despite this, he continued to cater to the well-to-do. Around 1923-1924, he designed an apartment building with a fabric store for the Dewaele family, who were textile merchants.

Typology

The Versatile Architecture of Charles Pil: A Diverse and Comprehensive Portfolio

Charles Pil’s architectural legacy spans an impressive array of projects, showcasing his remarkable versatility. While his expertise in designing homes for the affluent bourgeoisie stands out, Pil did not confine his talents to this niche. From the outset of his career, he tackled a variety of commissions, including hotels, apartment buildings, shops, public structures, and convents.

School Buildings

Charles Pil emerged as a notably active architect in the realm of school buildings, serving both governmental and religious organizations. The demand for new schools, expansions, and renovations surged due to several factors: the rise of Catholic schools after the 1831 establishment of educational freedom, the emergence of a liberal counter-regime in 1878, and the increasing emphasis on education in tandem with population growth. This trend further intensified with the introduction of compulsory education in 1914 and the necessity to rebuild schools devastated by World War I.

Pil’s school designs were tailored to meet evolving educational needs, prioritizing hygiene, sanitation, lighting, ventilation, and functionality. The separation of school and private spaces (such as teacher’s residences) became increasingly standard, a principle Pil consistently adhered to. His architectural styles ranged from sober designs to neogothic influences.

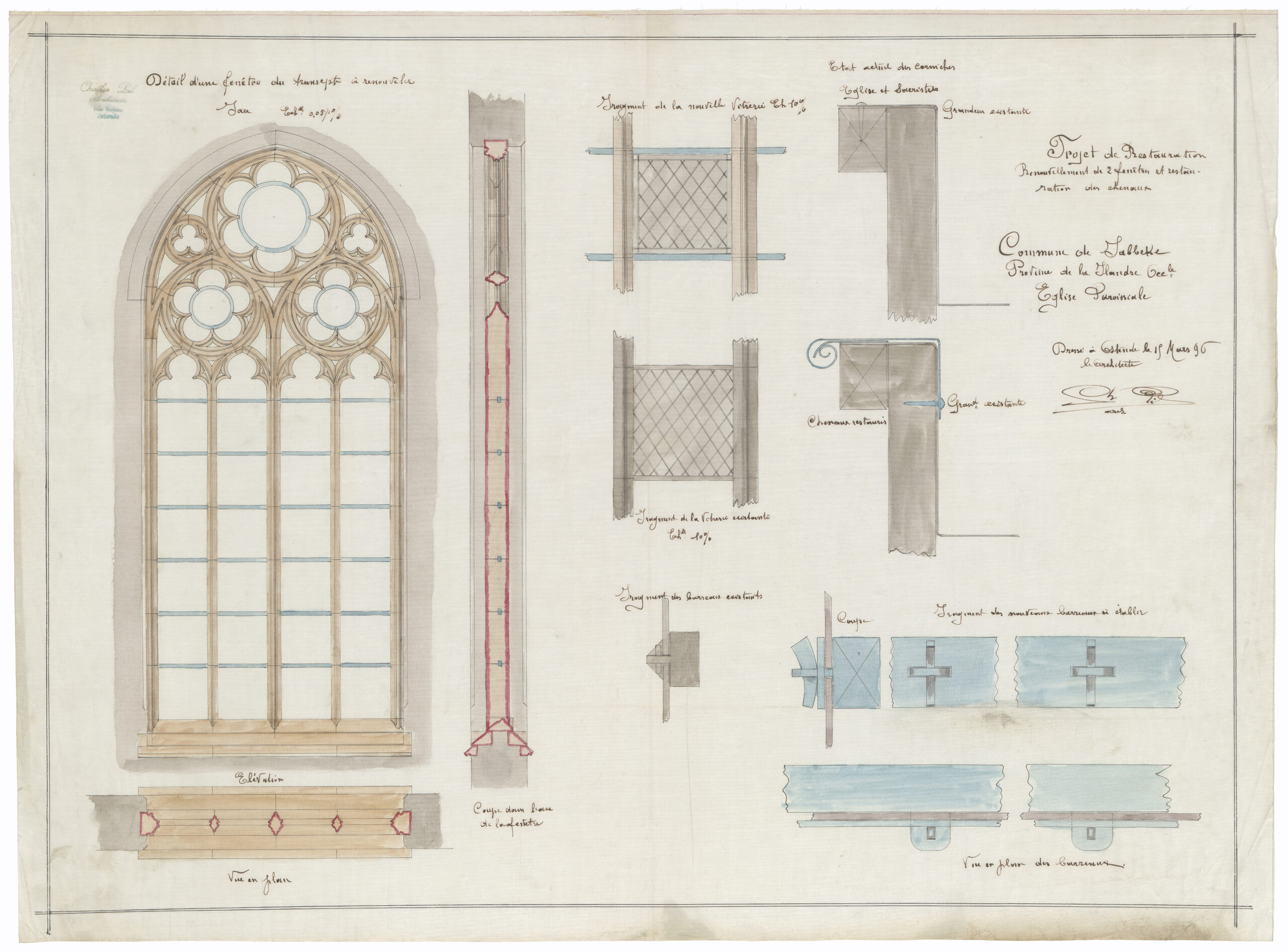

Religious Architecture

Educated at the Sint-Lucas Institute, renowned for its focus on Christian culture and artistic forms, Charles Pil frequently received commissions from religious institutions. Early in his career, he served as a restoration architect for two lancet windows in the neogothic Sint-Blasius Church in Jabbeke. By 1903, Pil had received commissions for a new deanery in Gistel, a boarding school for the Sisters of the Sacred Heart in Ostend, and a convent with an adjoining school for the Sisters of Saint Joseph, also in Ostend.

After World War I, Pil, in collaboration with Henri Carbon, played a crucial role in the reconstruction of numerous churches, rectories, and convents. Their partnership extended beyond reconstruction, involving many new construction projects that highlighted their versatility and craftsmanship.

Public Buildings and Infrastructure Works

Various local authorities in West Flanders sought Pil’s expertise for a diverse range of projects, including town halls, police stations, mortuaries, and almshouses. His portfolio also includes the establishment of oyster banks and the creation of memorials, further demonstrating his wide-ranging impact on the architectural and cultural heritage of the region.

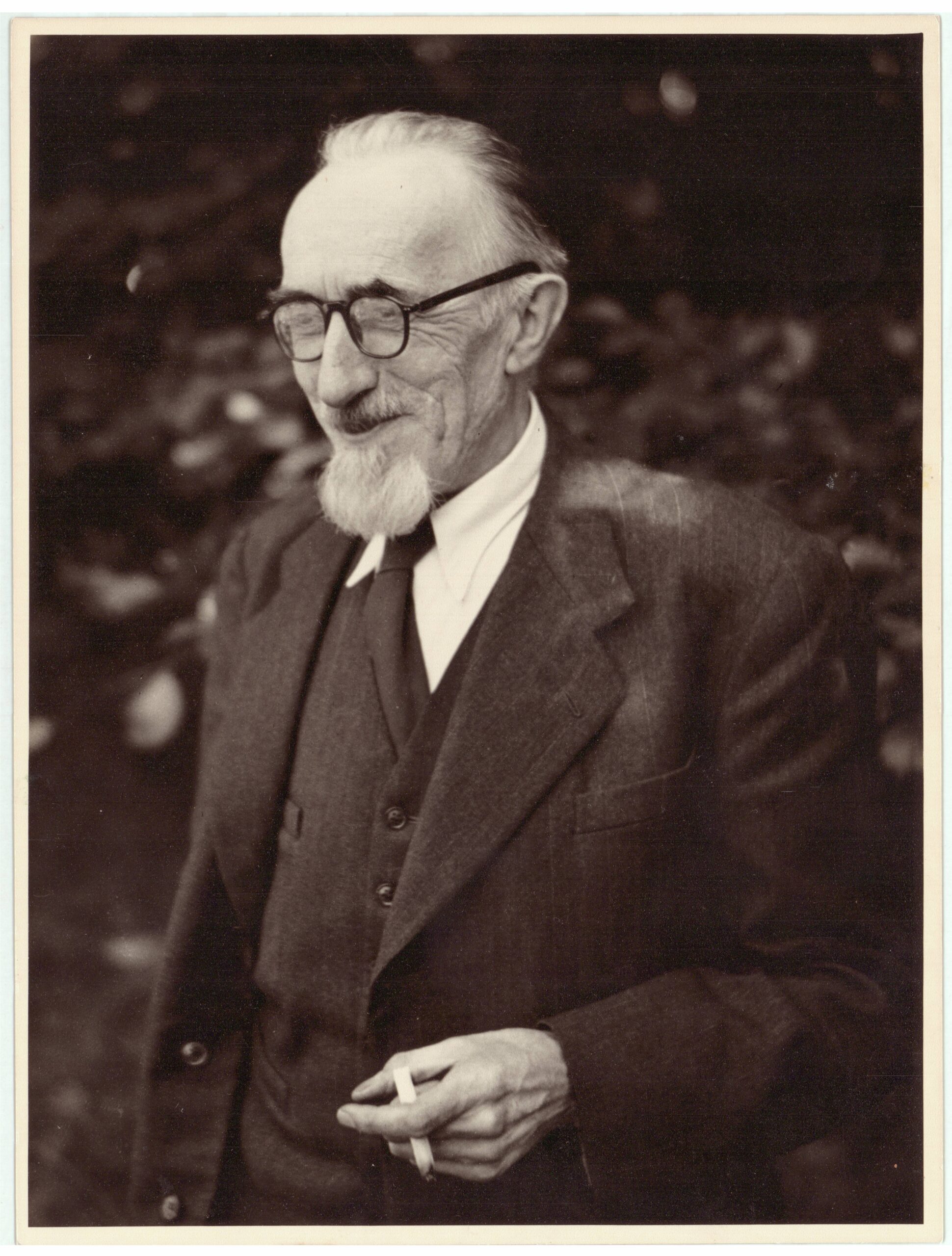

Henri Carbon

Pil and Carbon, an inseparable partnership?

In the aftermath of World War I, architects Charles Pil and Henri Carbon, despite their diverse backgrounds, formed a collaborative partnership that left an indelible mark on the architectural legacy of the region. Their joint efforts in designing and reconstructing buildings in the post-war era made it challenging to attribute specific contributions to either architect, as their works were consistently co-signed. This partnership extended beyond the borders of Ostend, actively contributing to the large-scale reconstruction of the front region.

Henri Carbon grew up in an artistic environment. His father, Clemens Carbon, came from a family of linen weavers and showed remarkable artistic talent from a young age. Supported by prominent village figures, Clemens developed into a skilled sculptor, primarily focusing on church commissions. After living in Roeselare, Clemens moved to Sint-Jans-Molenbeek. In 1867, he married Theresia-Virginia Laigneil, a well-to-do young woman, and they had five sons and four daughters. The third daughter, Paulina, later married architect Joseph Viérin. Henri (Hendrik) Carbon, the fifth son, was born on July 30, 1882.

Details of Henri Carbon’s education remain unclear. During his teenage years in Sint-Jans-Molenbeek, he apprenticed under his brother-in-law, architect Jozef Viérin, working on the beautification and expansion project of Nieuwpoort’s city center. After several years in Nieuwpoort, Carbon established himself in Ostend around 1911, maintaining his office there until approximately 1935. However, from 1922 onward, he resided in Gistel. On January 20, 1909, Henri Carbon married Juliette Vanderlinden in Ghent, and the couple had six children.

Before partnering with Charles Pil, Carbon had already completed various independent commissions. Notable projects included the now-vanished Katholieke Volkshuis (Catholic People’s House) in Ostend (1913) and several eclectic townhouses and cottage-style villas in Duinbergen (Knokke-Heist). In his later career, Carbon oversaw expansion works at the Abdij Ten Putte and the construction of the municipal school in Gistel.

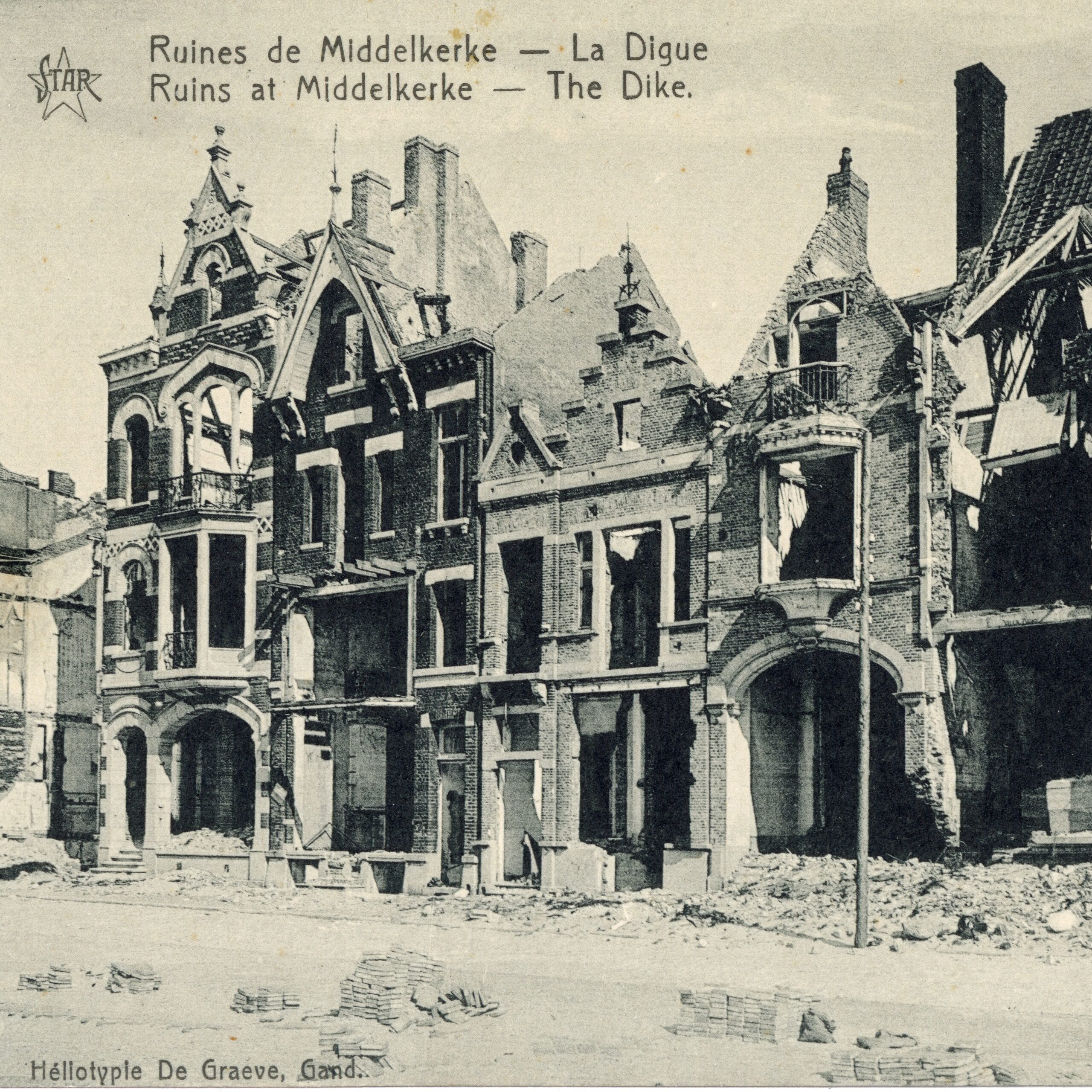

Reconstruction

Transforming Devastation into a Vast Construction Site

After the devastating First World War, West Flanders faced immense challenges in restoring a landscape heavily scarred and ravaged, while confronting the irreparable loss of its rich and diverse heritage. Cities like Ypres, Nieuwpoort, and Diksmuide emerged almost entirely destroyed from the war. The damage extended beyond the front region, inflicting deep wounds across the area. Architects like Charles Pil and Henri Carbon played crucial roles in the reconstruction, contributing significantly to resurrecting the landscape from its ashes.

Even during the war, policymakers convened to discuss the recovery of the devastated regions. The unprecedented scale of destruction compelled the Belgian state to both guide and organize reconstruction efforts. Two crucial laws served as guidelines for this monumental task. The decree-law of October 23, 1918, regulated the right to compensation for war damage. Restoration costs—though not necessarily to the original state—would be reimbursed and individually settled with each property owner. The Adoption Law, or Law on Assumed Municipalities, of April 8, 1919, provided a solution for municipalities that saw over 10% of their territory destroyed and lacked the financial means for reconstruction.

These municipalities could be “adopted” by the government. The Belgian State covered the costs of restoration in exchange for intervention, with the adopted municipalities coming under the supervision of one of the five High Royal Commissioners, who wielded extraordinary decision-making powers. The administrative and financial oversight of reconstruction rested with the Service of Devastated Regions, established in April 1919.

Gradually, reconstruction took shape. Initially, the priority was to restore essential roads and public transportation, and to reconstruct central squares, town halls, schools, and other public facilities. The full recovery of homes gained momentum several years later, and the construction of larger buildings, including churches, took even longer. Once plans were approved and compensation determined, construction projects could be publicly tendered.

The Reconstruction Architect: A Multifaceted Role

During the reconstruction period following World War I, it was not a given that every building would be designed by an architect. The architectural profession had not yet been formally recognized, with legal protections only coming into effect in 1939. An architectural diploma was not mandatory, and many homes were constructed without architects, often built by masons. Given that approximately 38% of homes in West Flanders were completely destroyed, appointing an architect for each house was unfeasible.

Despite this, nearly every local architect contributed to the reconstruction efforts. Designers and urban planners from Brussels and other parts of Belgium also played crucial roles. The term “reconstruction architect” encompassed hundreds of professionals, with over 250 architects participating in the rebuilding efforts.

After the war, Charles Pil and Henri Carbon joined forces, forming an exceptionally active duo that played a crucial role during the reconstruction period. Their influence extended across West Flanders, where they were responsible for rebuilding numerous public buildings, a task allocated by the High Royal Commissioners. The architectural education of Pil and Carbon, their practical experience, and their close ties to other prominent architects like Jules Carette and Jozef Viérin undoubtedly helped secure these commissions.

Charles Pil and Henri Carbon left an enduring mark on the architectural landscape of various villages after the war, including Lo-Reninge, Middelkerke, and Nieuwpoort. They designed a wide range of buildings, from government structures like town halls and schools to religious buildings such as churches and rectories. Their work also included numerous private buildings, spanning coastal villas, townhouses, and rural homes.

Balancing Historical Re-creations and Historically Inspired Designs

During the First World War, reconstruction planning commenced even before the war ended. Various perspectives surfaced, including Winston Churchill’s proposal to preserve ruins as memorials and construct new cities elsewhere. In Belgium, architect-photographer Eugène Dhuique supported this notion, viewing identical reconstructions as historical distortions. Contrarily, Joris Helleputte—Minister of Agriculture and Public Works and an architecture professor—championed authentic reconstruction. This debate engaged city architects such as Jules Coomans in Ypres and Jozef Viérin in Nieuwpoort and Diksmuide, who advocated for historically inspired reconstructions, reflecting the Sint-Lucas Schools’ traditions. Ultimately, historically informed reconstruction became widely accepted, fulfilling local communities’ desires to restore familiar landscapes and heritage, while addressing practical needs like property structures and avoiding extensive expropriation.

Architect duo Pil and Carbon designed numerous buildings. For significant structures like churches, rectories, or town halls, they often chose historical and fairly authentic reconstructions. For new residential buildings, they primarily created fresh designs influenced by historical styles. Using traditional materials like brick, they drew inspiration from 16th and 17th-century Gothic architecture. Features included rectangular window openings with segmental arches, elaborate chimneys, and dormers with stepped or gabled roofs.

Reconstruction did not necessarily mean returning to pre-war housing. War-affected owners could improve their homes aesthetically and hygienically or modify property boundaries as needed.

Interior

Determining Charles Pil’s precise role in interior design and decoration remains a challenge. Pil began his career during the belle époque period, a time when attention primarily focused on facades, which served as calling cards displaying the client’s status. However, part of the interior was also considered a significant social space where representation played a crucial role.

Interior Design and Layout in Charles Pil’s Architecture

Behind the facades of Pil’s townhouses, a similar spatial layout often emerges. He adopted the traditional 19th-century floor plan, featuring a central hallway flanked by reception rooms on either side. The key spaces for representation—the street-side salon and the garden-side dining room—were connected by double doors, allowing guests to move directly from the salon to the dining area. The staircase typically stood near the main entrance, inviting admiration from visitors. These grand staircases, often with majestic inclines, were divided into two flights and a landing per floor. Bedrooms occupied the upper levels, while the attic housed staff quarters. In the 19th century, the kitchen’s location was a topic of debate, sometimes situated in semi-subterranean cellars alongside wine and coal storage or adjacent to the dining room.

Fixed interior elements

Preserved specifications reveal that Charles Pil paid attention to interior furnishings. These documents mention various fixed interior elements, including tiled floors, parquet, doors, and other carpentry. Detailed drawings, such as those of doors and windows, have also survived, providing deeper insights into room decoration. Interior doors were typically paneled, crafted from “red Nordic pine of first choice” or oak.

Restauration

Preserving for the Future: An Advocacy

Charles Pil’s extensive body of work includes many buildings that have endured over time. However, his architecture faces diverse challenges, ranging from urban renewal to evolving requirements related to energy efficiency, comfort, sustainability, and even changes in function or program. Many of his structures are integral to the urban fabric, contributing to the identity and character of the cities and municipalities where they stand. Yet, their significance extends beyond visual impact alone.

Pil’s buildings tell stories of their era—the zeitgeist in which they were conceived—and the clients and users involved. His townhouses and villas evoke the grandeur of bygone times, while the reconstruction projects reflect the horrors of war and subsequent recovery.

Despite these challenges, opportunities exist for sustainable reuse. Various restorations and renovations demonstrate that elements from the past can harmonize with contemporary needs, resulting in high-quality projects.

Gistel

The Deanery of Gistel

On November 4, 1903, Pastor-Dean Victor Cambier and assistant priests Medardus Van Hoonacker and Camillus Meysman each laid a stone in the front facade of the new deanery in Gistel. Their names and the year were inscribed on the bricks, marking the construction of one of the three projects that Charles Pil realized in Gistel. These projects were largely due to his political connections, as Pil had run for municipal office in Ostend on the Catholic list in the 1895 elections. His support came notably from Victor Cambier, the pastor-dean of Gistel and chairman of the regional Catholic Voters’ Association.

The 1903 deanery is a prime example of Charles Pil’s Neo-Gothic work. As early as January 1896, Pastor-Dean Cambier had expressed a desire to build a new deanery because he considered his current residence uninhabitable. However, due to budget constraints, the project did not commence until 1901. Eventually, under the pressure of Mayor Delphin Depuydt, the municipal council approved the plans and specifications on December 11, 1902, with an estimated cost of 31,272 francs.

Tielt city architect Gustaaf Hoste was involved in the project due to his appointment for the planned construction of a new spire for the Church of Our Lady in 1905, later nicknamed “the Golden Tower” by the people of Gistel. The diocesan archivist, Michiel English, was critical of Pastor-Dean Cambier, accusing him of selling numerous art treasures to fund his ambitious construction projects.

Pil faced a challenging task in creating the plans, as he had to consider comments from Bishop Gustaaf Waffelaert, the permanent deputation, Minister Jules Van den Heuvel, and Governor Jean-Baptiste Bethune de Villers. The latter even sent Pil a sketch with an explicit request to design the facade in a style he termed “Gothic architecture.” During this period, we know from the birth certificate of Pil’s daughter Edith (1901) that he lived nearby on Bruidstraat.

The construction projects for both the spire and the deanery caused financial concerns for the municipal government. A loan of 60,000 francs over ten years was taken out with the Board of the Poor. Pastor-Dean Cambier’s building fervor divided the community for a long time, leading to incidents such as the tar smearing of the deanery’s facade and a nearby tavern in 1906. The municipal government offered a reward of 200 francs for information but to no avail. The people of Gistel quickly nicknamed the building “the Little Vatican.” Even during the 1912 election campaign, the construction of the deanery remained a contentious issue between Catholics and liberals.

School Construction

A second project by Charles Pil was the expansion of the boys’ municipal school and the renovation of the head teacher’s house. The municipal council approved Pil’s plans and specifications on December 23, 1908. The expansion, which added two classrooms, was based on a study that found the student population had increased to 280. The local contractor and carpenter August Devos won the tender for the price of 29,290.15 francs, and the work was completed on April 1, 1911.

For completeness, it should also be mentioned that in 1932, Charles Pil collaborated with Henri Carbon on the construction of classrooms for the fourth grade of the accepted girls’ school in Moere. It was Pastor Hector De Gryse who urged the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Vincent de Paul of Eernegem to expand the school complex, which dated back to 1882. Under the administration of Alfred Ronse, first as alderman and later as mayor, Pil received no further assignments in Gistel. Ronse preferred to work with architects Theo Raison and Henri Carbon.

Henri Carbon in Gistel

Architect Henri Carbon moved to Gistel in 1922, where he had a house built with a clear regionalist influence along the Komvaart. Regionalism, the dominant style during the reconstruction, is characterized by the use of local materials, techniques, and stylistic elements. Carbon named his house “De Boomgaard” (The Orchard), a reference to the vanished castle site with a motte, as indicated on the “Plan der Stede en Graefschap van Ghistel” drawn from the perimeter made in 1678. Key features of this house include stepped gables with corbelling, decorative anchors, and woodwork with small-pane windows. Just before 1960, “De Boomgaard” briefly served as the town hall and housed the magistrate’s court for the canton of Gistel.

Thanks to the influence of Mayor Alfred Ronse, Carbon was able to carry out many projects in his hometown, some of which still shape the streetscape today. For the execution, he mainly collaborated with local entrepreneurs such as Gustaaf Boudolf, Gistelse Werkhuizen, Germain De Smet, Kamiel Sanders, and Jules Coppens.

At the request of the church council and Pastor-Dean Alfons Bruyneel, Carbon realized a new parsonage in Bruidstraat around 1939, executed in a simple regionalist style. A few years earlier, he had also designed the chapels for a procession route around the Church of Our Lady. For the ceramic scenes from the life of Saint Godelieve, he enlisted the help of Jules Fonteyne, the director of the Bruges Academy. In 1942, Carbon also designed a plan for the expansion of the cemetery.

A significant client of Carbon was the Congregation of the Sisters of Mary of Pittem. Until 1943, there were difficult negotiations with the superiors, Bertha Cardoen and Marie Catry, about his fee. They repeatedly asked the architect to reduce his fee and donate the difference to their Congregation’s missionary work. In 1937, Superior Cardoen decided to build a new convent, a chapel, a rest home, and a farm.

The convent and rest home became landmark, imposing brick buildings with a regionalist style, visible in the facade, which is interrupted by stepped gables with Bruges window bays. At the rear, a simple chapel with a cruciform plan was erected, dedicated to Our Lady Mediatrix. The first stone was laid in May 1937, and on August 13, 1938, the chapel was consecrated by Alfons Bruyneel. However, after a bomb impact in May 1940, Carbon had to draw up a specification for the thorough restoration of both the rest home and the convent on September 17, 1941.

At the request of Superior Catry, Carbon, a year before his death and as one of his last assignments, designed a plan for the construction of six classrooms, a playground, and a covered courtyard for the accepted girls’ school. In 1941, at the request of wartime Mayor Prosper Vereecke, he drew up a preliminary design for a new municipal school. Due to wartime circumstances, this project was never carried out.

With the abbey’s title obtained in 1934, Abbess Placida de Keuster unfolded her plans to thoroughly renovate the Neo-Gothic convent by architect Jean-Baptiste Bethune. Alfred Ronse, the monastery’s syndic, requested Carbon to prepare the necessary plans. In 1934, the construction of an extensive west wing began, followed by a series of repairs between 1937 and 1941, including the restoration of the refectory and tower, the addition of a new sisters’ choir with choir stalls, a cloister, a chapel, and a sacristy. For the design of the sisters’ choir, with an impressive stained-glass window by Joost Maréchal, Carbon closely collaborated with his brother-in-law Jozef Viérin and sculptor Leo Speiser. Together with Viérin, he also designed a new chapel for the “Hemd zonder Naad” (Seamless Robe) in Abdijstraat. After Carbon’s death in 1950, Arthur de Geyter continued the extensive renovations of the abbey, particularly noting the changed liturgical orientation of the church.

Colofon

Exhibition: Charles Pil 1867-1949

June 29, 2024 – December 11, 2024

A collaborative effort by the city of Oudenburg and IOED Polderrand, in partnership with:

- Municipalities: Nieuwpoort, Middelkerke, Gistel, Lo-Reninge

- Cross-regional cultural and heritage collaborations: Ginter, Hydra, IJzervallei

- Local heritage associations: Erfgoedkring 8460 (Oudenburg), Graningate (Middelkerke), De Plate (Ostend)

- Guides association: Lange Nelle

- VIVES University College

- CultuurContaCt In Dialoog

Exhibition Details:

- Coordination: Wouter Dhaeze (City of Oudenburg) and Joke Meerkens (IOED Polderrand)

- Contributors from Working Groups:

- Gistel: Filip Debaillie, Werner Peene, Klaas Staelens, Marc Vansevenant

- Lo-Reninge: Neno Clynckemaillie, Chris Vandewalle, Elke Verbeke

- Middelkerke: David Stuyck, Ronny Van Troostenberghe, Simon Vosters

- Nieuwpoort: Tom Bellefroid, Eveline Denorme, Fien Hellebuyck

- Ostend: Dirk Beirens, Norbert Hostyn, Nadia Stubbe

- Oudenburg: Lucien De Cleer, Sarah Kesteloot, Werner Peene, Fré Vanhooren

- Texts: Joke Meerkens (coordination), Tom Bellefroid, Jade Duysan, Fien Hellebuyck, Sarah Kesteloot, David Stuyck, Chris Vandewalle, Marc Vansevenant, Ronny Van Troostenberghe

- Tekst Editing: Wouter Dhaeze, Joke Meerkens, Sarah Kesteloot

- Image Credits: General State Archives (Brussels), Archives Diocese of Bruges (Bruges), Archives Provincie West-Vlaanderen (Bruges), Archives Hogeschool Sint-Lucas Gent (Leuven), Image Bank Flanders Heritage Agency, Image Bank Heritage Bruges, Image Bank Coastal Heritage, Image Bank Souvenhiers, Collection Erfgoedhuis Bachten de Kupe (Koksijde), Photographic Collection of the City of Ostend, Municipal Archives Middelkerke, Royal Commission for Monuments and Sites, Ostend Digital Publications,Private archive Erwin Mahieu, Private archive Filip Debaillie, Private archive Marc Vansevenant, Private archive Ronny Van Troostenberghe, Private archive Pieter Carbon, City archive Nieuwpoort, City archive Ostend, City archive Oudenburg

- Lenders: Pieter Carbon, Filip Debaillie, Erwin Mahieu, Guy Servaes, Marc Vansevenant

- Photo Credits: Willy Bulteel, Eddy Christiaens, Thierry Caignie, Johan Degraeve, Edwin Fontaine, Norbert Hostyn, Peter Maenhoudt, Guy Servaes, Hilde Vanhove, Chris Vandewalle, Greta Van Rompaey

- Podcast: Ellen Rooms (coordination), Tom Bellefroid, Dirk Beirens, Sjaak Bisseling, Willy Bulteel, Neno Clynckemaillie, Geert Dewachtere, Lieve Dewicke, Torsten Feys, Dirk Halewyck, Joke Meerkens, Lode Morlion, Michel Roobrouck, Nadia Strubbe, Claudine Vandendorpe, Chris Vandewalle, Delphine Vanoverberghe, Ronny Van Troostenberghe, Elke Verbeke

- Technical Execution: City of Oudenburg, technical department

- Design: Gils Baekelandt, Katia Braeckevelt, Kjell Debeuf, Lara Matijasic, Feke Meeuws, Iris Ruckebusch, Annelies Siersack, Kyana Vermussche (VIVES), Ellen Rooms, Elke Verbeke

- Printed by: Motief

Photography Exhibition

- Curators: Wouter Dhaeze, Joke Meerkens

- Photographers: Willy Bulteel, Eddy Christiaens, Johan Degraeve, Hilde Vanhove, Greta Van Rompaey

With support and collaboration from various partners.